Wrath-Kindled Gentlemen

In 1975 Michel Foucault told a left-wing activist “Chile’s tragedy is not the result of the Chilean people’s failure, but the result of the serious mistakes in the monstrous responsibility of you, Marxists.”

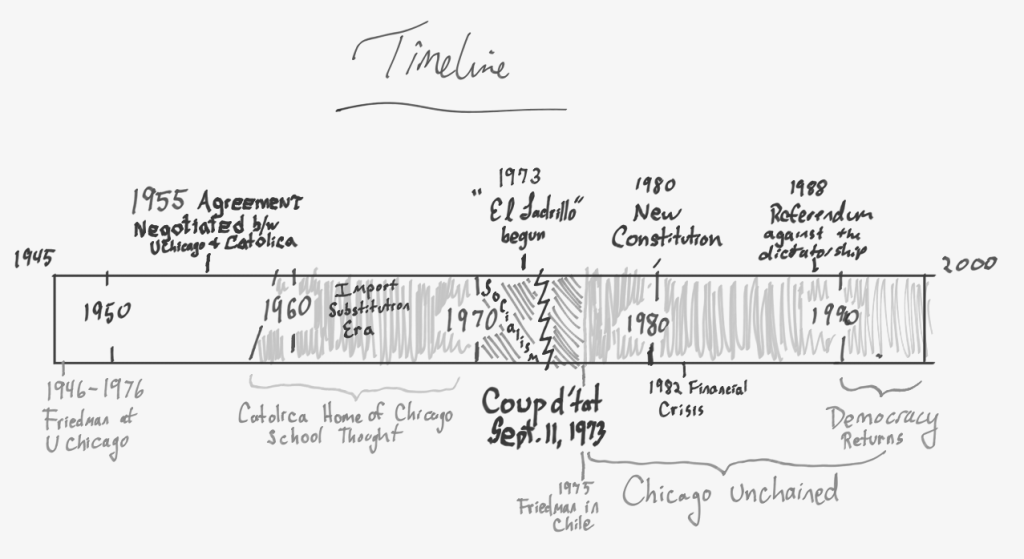

Two years earlier on July 29th, 1973, the Second Armored Regiment of Chile rolled six tanks and several trucks into downtown Santiago towards the presidential palace to overthrow the government. Soon a host of other military units would join them to bring down the socialist government of Salvador Allende, which had taken a wrecking ball to the nation’s already precarious financial stability. The other military units did come, but not to join them; those units that put down the coup and restored democratic order were led by none other than Augusto Pinochet.

44 days later on September 11, 1973 that same general, now commander-in-chief Augusto Pinochet, would himself be leading the coup against the government. What could cause such a shift? Was it merely the insubordination of the Second Armored Officers? Or did something change between July and September? I see several reasons that could explain his shift beyond the obvious.

Firstly, the government elected in 1970 had taken farms, factories, and the world’s largest copper mine from the hands of private owners without compensation. They took direct control of nitrate, telecom companies, banking, insurance companies, “monopolistic” manufacturing, and foreign trade. The unions would go on strike at a company and the government would declare the company distressed and seize control. The dubious legality and overt ideological motivations of the government made the military uncomfortable.

Chilean firms with US financial support had tried to prevent the Marxist government from taking office in 1970. But the only result was murderous anti-communists got as far as killing a General whom they tried to kidnap. Other attempts at stopping the transition of power through the legitimate political means failed, but together the violence and attempted political maneuvers had reinforced the tragic revolutionary/counterrevolutionary dynamic of the Cold War. The Allende government tightened its grip and clenched its teeth to bear down on their ruinous agenda.

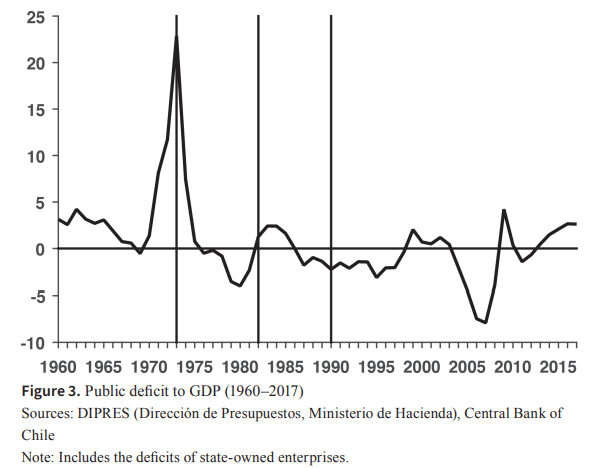

Secondly, the economy under the Finance Minister and union leader Américo Zorilla, a man with a high school degree and no economics training, was in a tailspin. Inflation had passed 300%. Foreign investment disappeared. Exports plummeted. Fernando Flores took control of the Finance Ministry in 1972, inflation hit 500+%. The paychecks of the military were at stake as well. Even in 1969 during the prior government, some soldiers led a demonstration about low pay. Everyone was striking. Doctors were striking. Miners were striking. Even the domestic workers were striking.

Thirdly, sheer inevitability. There had already been one military coup attempt by lower officers (two if you count some abandoned 1970 plans). Now on August 22nd, the lower chamber of congress acknowledged that the military and government were on a collision course. They sided with the military. In that August 22nd legislation, the lower house outlined the abuses of the Allende government and voted 81- 47 that military “presence must be directed toward the full restoration of constitutional rule and of the rule of the laws of democratic coexistence, which is indispensable to guaranteeing Chile’s institutional stability, civil peace, security, and development” and thus it “is their duty to put an immediate end to all situations herein referred to that breach the Constitution and the laws of the land with the goal of redirecting government activity toward the path of Law and ensuring the constitutional order of our Nation and the essential underpinnings of democratic coexistence among Chileans.”

Sounds like permission to do a coup.

A few weeks earlier towards the beginning of August, Allende appointed the Army’s General Pinochet to commander-in-chief of the armed forces after the previous commander resigned. According to one of Salvador Allende’s biographers, Victor Figueroa Clark, the coup was a matter not of if, but when. The bloody pendulum of military usurpation was already swinging down to strike its blow against the incompetent regime. The only question for Pinochet was whether he would align with this inexorable force.

In the darkness of morning of September 11th the coup was officially launched. The Navy returned to port during a military exercise. By mid-morning, the government understood that a full scale coup was in effect. Allende tried to call Pinochet multiple times to come save the government from the mutinous navy. “Poor Augusto, he must be under arrest,” Allende is reported as saying. Allende learned soon after who the poor man must be. It was not Pinochet.

Although he refused to surrender or to go into exile, Allende made a final radio speech to his comrades and friends and well-wishers around the world and bade adieu. In several ways, revolutionary socialism died by its own hand. Military dictatorship and the secret police followed.

Such drama demands a screenplay.

Out of three top hits for YouTube documentaries, not one mentions the state of the economy, nor the congressional resolution (of debatable legality, but interesting and important nonetheless!), nor the prior coup attempt. In one, Cambridge’s Nicholas O’Shaughnessy simply asserts that Allende’s policies were “no different from the social welfare policies of northern European nations.” Does that hold up to scrutiny? Ubiquitous price controls do not a successful Sweden make. One excellent audio documentary series, The Santiago Boys, never gives the impression that Allende’s own policies were to blame for the economic tailspin. It’s always Nixon, Kissinger, and ITT (International Telephone & Telegraph) or the vague and unjustified ideological animosity of of the military establishment and “capitalists” towards Allende.

Historical memory has settled on a misleading hagiography. The drama is better than that! It’s a Shakespearean drama: Richard II and Henry IV. We have Allende’s radical quixotic socialism with dire consequences for economy and democracy – as well as Pinochet’s sudden betrayal and violent political oppression combined with the eventual turn towards economic freedom.

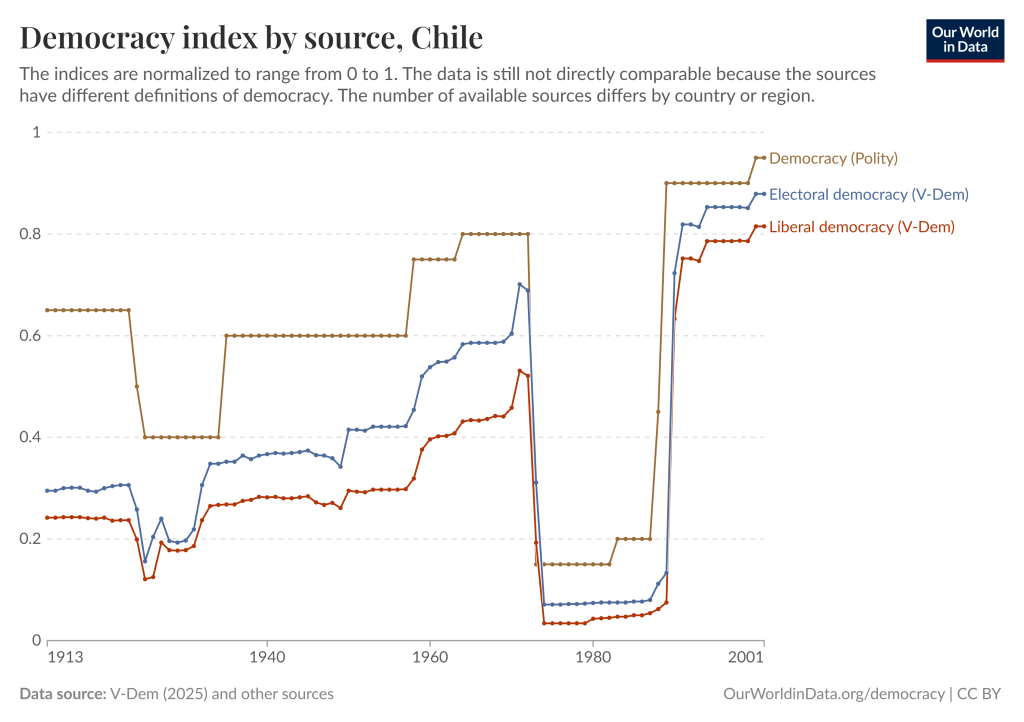

Mixed emotions of catharsis and woe, of relief and horror, of wonder and awe would be much more appropriate reactions to the political degradation and economic history of Chile.

The Chile Project

How did a dictator in Latin America wind up deploying the economic reforms of a Margaret Thatcher four years before she came to be prime minister?

It goes back to the University of Chicago, which trained Chilean economists as part of a program called “The Chile Project.” This government-funded project launched in 1955 was meant to provide aid to Chile. George Shultz one of the leaders of the program told the US Government that he didn’t know how to run an aid program. But he knew how to teach economics.

An agreement was negotiated with the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile (Católica) for graduate students to come to Chicago to learn economics. In exchange the students would teach at Católica for at least two years. Chicago Economics Department Chair Theodore Schultz and economist Arnold Harberger ran the program.

The Chicago Boys, as they are called, were a collection of the Chilean students who would modernize the economics department at Católica. They replaced such horrors as a capstone class in Mercería in which students would learn to identify cloths by touch so as to impose the correct tariff on them with more becoming courses on price theory, exchange rate equilibria, contract theory.

The students matriculating into Chicago were not particularly ready for the modern economics graduate curriculum and took mid-level undergraduate courses as well. There they read the first eight chapters of Alfred Marshall’s Introduction to Economics as well as Penny Capitalism: A Guatemalan Indian Economy by Sol Tax and the labor market work by Chile program director H. Gregg Lewis.

Back in Chile these students turned into demanding professors. Sergio De Castro, Emilio Sanfuentes, and others taught and wrote and researched at Católica. In 1963 they founded a research journal Cuadernos de Economía Notebooks on Economy. Pablo Baraona and Ricardo Ffrench-Davis were the editors.

In 1965, a think tank, Centro de Estudios de Sociales y Economía sprung up. Emilio Sanfuentes took over the economics wing of the think tank. The think tank was promoted by Augustín Edwards who also owned the largest newspaper El Mercurio which opened up a column on finance and economics. There popular versions of economic arguments could make a public play. In a three year period (1967-1970) the Chicago Boys and allies pumped 170 articles into the market friendly El Mercurio, putting their ideas into the arena of praise and ridicule and denigration.

El Mercurio was one of a small handful of media organizations that continued to get an additional subsidy via the United States’ CIA which feared, just as the newspaper’s owner did, a wave of Cuban-like revolutions sweeping Latin America.

During the 1970 presidential campaign a few of the Chicago Boys were asked to draft an economic proposal for the Jorge Alessandri campaign. Allegedly, the proposals were so radical in the eyes of the industrialist that he exclaimed, “Get those crazy men out of here; and make sure they never come back.” Nonetheless, the practice of writing a policy brief would be put to good use.

“Cybernetic Socialism”

Meanwhile in Allende’s government expropriation of businesses, massive state control of prices, and expansive social spending was supposed to bring about a new Republic of “endless wine and empanadas.” It was not working so well. The economy tanked (stats!). What to do?

Allende’s government was drowning in the struggles of owning the economy. If only there was some system for dynamically allocating goods and efforts under conditions of scarcity. Discover bottlenecks, push out productive possibilities frontier… It sounds like a job for the budding field of cybernetics! They called up British cybernetic consultant Stafford Beer of “the purpose of a system is what it does” fame. Stafford Beer would build the system that would save not only the economy but Allende, socialism, and the future of civilization: “cybersyn,” a dream of cybernetic socialism

Even today the romance hasn’t worn off. Evgeny Morozov writes “The Santiago Boys… try to wrestle control over technology from multinationals and intelligence agencies and use it to create a more egalitarian economy.” But narrative framing only goes so far. What is really needed to be wooed by the forces of cybernetic socialism is the wonderful mock-up of the economic control room.

It’s the Jedi council for philosopher-kings. Nous sommes l’État.

Thanks to the invitation of economist Fernando Flores, Stafford Beer comes to Chile and will save the day. First stop: the center for economic planning, Ministeria Economia. There he wants to learn what models are being used to set prices. Actually, there are no models. Businesses propose a new price, the ministry approves a smaller mark up, and they go back and forth like that. Sometimes files are “misplaced”, or expedited, or easily approved, or given special scrutiny. Depends of course on favors. Beer wants to know how general equilibrium effects are calculated. Well, they aren’t.

A mathematician in the ministry offers to be helpful. We have a computer which can calculate cross-sector supply requirements. “How many industries are included in the model?” Beer asks. The young mathematician says something like 50 or 15. The translator clarifies that it is 15. Beer, “But, my friend, you really want to determine true, social equilibrium pricing for 3,000 goods with a 15 sector input-output matrix?”

Alas, before the dream of cybernetic socialism could be realized (or even wrestle down the union leaders who objected to quantification of worker ops) Cybersyn was destroyed along with the Allende government. It had connected 12 telex machines to the main hub of a 64kb memory IBM 360 Model 50. Such rigs existed already around the world. But what made this one distinct is not that it was socialists pre-empting the Internet, but rather that it was in the service of a centralized economy. They succeeded in mapping the operations of a handful of factories. The knowledge problem went uncracked.

Origins of New Economic Policy

In December 1972 a retired Navy Officer Roberto Kelly and Admiral Toribio met and agreed that if the government was going to be toppled the military needed an economic plan so that they could get out of the economic mess. Kelly knew Emilio Sanfuentes at the Centro de Estudias Sociales y Economia would be right for the job. He approached Sanfuentes and requested a report.

Eleven economists got to work on a type of confidential white paper. 9 had Masters’ degrees in Economics from the University of Chicago, one from Harvard, one from Católica. Sanfuentes was the go between with the client, who was the Navy, and Sergio de Castro was main editor of the project.

The final document is known to history as El Ladrillo THE BRICK because it was so thick. Several inches, they said. The original name of the daring policy proposal was the very unobtrusive Programa de desarollo economico, A Program for Economic Development. I was personally disappointed to discover that the foundational document of Chilean economics only had 200 pages. For an Admiral in the Navy, though, that might be an intimidating amount: a veritable brick.

El Ladrillo has all the marks of a market based set of policy proposals written by people who were accustomed to integrating Catholic social teaching and motivations. And it came naturally. It was written by members from the Pontifical Catholic University who thought of economics as a moral science. For example, when discussing the difficulty of disbursing poverty relief, they acknowledge that in a poor country fact checking eligibility in advance will be very difficult and very expensive. But they reasoned that the optimal amount of fraud is not zero. It is preferable to have some fraud if it ensures that the poorest citizens of Chile are “able to live lives with some degree of dignity.”

The economists did not conceive or write about their project as a type of neoliberalism. At the time the term ‘neoliberalism’ was associated with German reforms under Adenauer. Instead they saw the Chicago project as a type of subsidiarity, the concept in mainly Catholic political theory that decisions should be made at the lowest possible level to solve problems. The decentralization of free markets naturally does this by allowing firms and decision-making to discover the right size for their purposes.

At the same time, the proposals found in El Ladrillo are the types of policies one would expect from modern economists taught by Gary Becker, Milton Friedman, and Arnold Harberger: tariff reduction, removing subsidies and government protections of industries, removing all price controls, decreasing fiscal spending, making the central bank independent, allowing the currency to float. The Chicago Boys had taught Marshall’s Principles and Friedman’s Price Theory at Católica. Inevitably those influences were a lion’s share.

Other specific influences include Albert Hirschmann, who had done a 1963 study on the history of Chilean inflation, and Al Harberger, who had done research on Chilean inflation dynamics.

Although not finished in the promised 90 days, the document was completed in time for the coup.

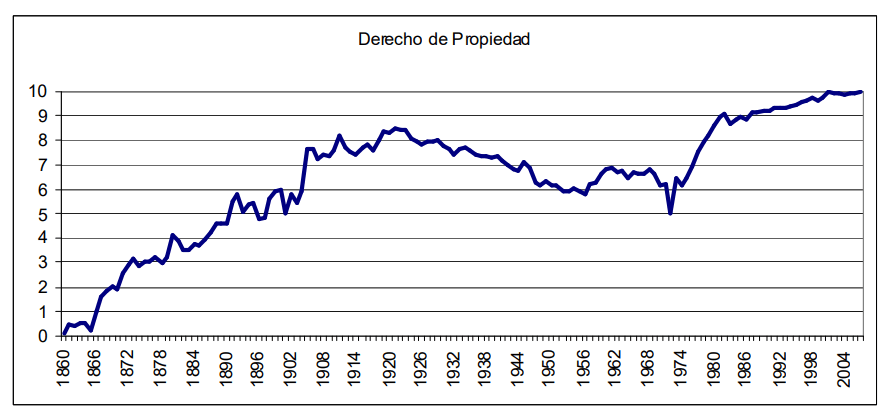

Above is a Yearly Property Rights scale based on a 1-10 Index, sc. Rodrigo, Saravia 2009.

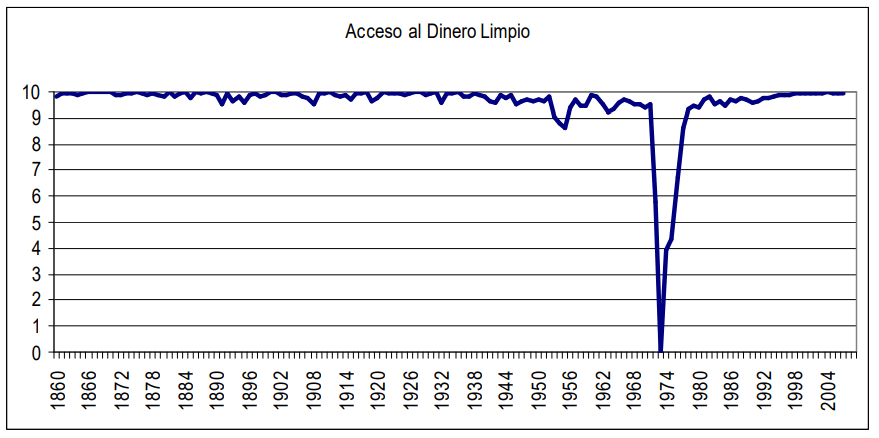

Above is an index of access to clean, unlaundered money on a 1-10 Index, sc. Rodrigo, Saravia 2009.

Three days after the coup Sergio de Castro was quickly appointed to the government as senior advisor to the military officer in charge of the economy, General Rodolfo Gonzalez. Gonzalez showed De Castro one of the 25 printed copies of The Brick and said implement this. In fact, De Castro knew the document well already; he had written it.

To fight inflation at almost 700% de Castro removed price controls on as many goods as the military would allow. (Always amazing how many goods become national security related, when you have the power to control their flow…) Nonetheless, thousands of goods started to have market floating prices. A cooking oil business shows up to de Castro’s office and requests a price increase on oil. They provide a well-prepared document showing the the need for a price increase. De Castro responds. “I don’t need to see this. Set the price to whatever you want.” The business leaders leave insulted.

They return a week later. “I don’t need to see it. Truly. Set the price to whatever you want. If you set it too high the oil won’t sell, if you set it too low, you’ll lose a lot of money.” The business leaders left confused.

They check in one last time. ‘Can we really set the price to whatever we want?’

Milton Friedman Speaks

Milton Friedman visited Chile three times, but it was his first visit that really mattered for him and for Chile.

If Fernando Flores tried to move the economy through the consultation of Stafford Beer, Rolf Lüders tried to do so through his famous invitation to his teacher Milton Friedman.

Milton Friedman had had some of the Chilean economists in classes, but mutual contact was not a big part of either of their lives. Though there was certainly indirect influence and much agreement between Friedman and the type of economic policies promoted by El Ladrillo (a document he didn’t know about), Friedman was not heavily involved with, nor in contact with, any of the Chilean economists except for Rolf. Nor did he serve an advisory role in any of their deliberations.

Nonetheless when he visited Chile for the first time in 1975, in my reading he had a big effect. Friedman along with Al Harberger met with Pinochet for 45 minutes. One condition of the meeting was Friedman wanted to be able to say whatever he wanted. Every interaction had the same drum beat. You need a price system, you need markets, in the current system there is massive waste because no one knows what to build and how much. People need freedom to choose their economic fates.

Friedman told Pinochet he needed to stop inflation through immediate fiscal austerity and that freeing finance, labor market, and prices was the only way to produce growth and reduce poverty.

Two days later, Friedman spoke to several hundred business people at an event organized by Rolf Lüders. He advocated the same immediate change of course in Chilean economy (end state owned enterprises, decrease tariff barriers) and then engaged in Q&A for over an hour. 22 questions were asked – some accusatory, some surprised.

And again he met with 200 military officers to tell them how to save their country. His drum continued to the same beat. End. Price. Controls. End them on Goods. On Labor. On Loans.

The Chicago Boys have gone out of their way to distance themselves from Milton Friedman as an influence and cause of their success. They were much closer to their friend and mentor Al Harberger. Nonetheless, based on the timeline of subsequent events, it seems that Friedman altered the political economy within Chile.

Within the military government there were two camps: the democratic leaning military leaders and the national security military leaders. The democratic leaning military leaders were more willing to release some power back to the private sector or the non-military public sector. The national security military leaders believed in a strong state that controlled many aspects of the economy and all of civil society, from universities to manufacturing, for national security reasons, of course.

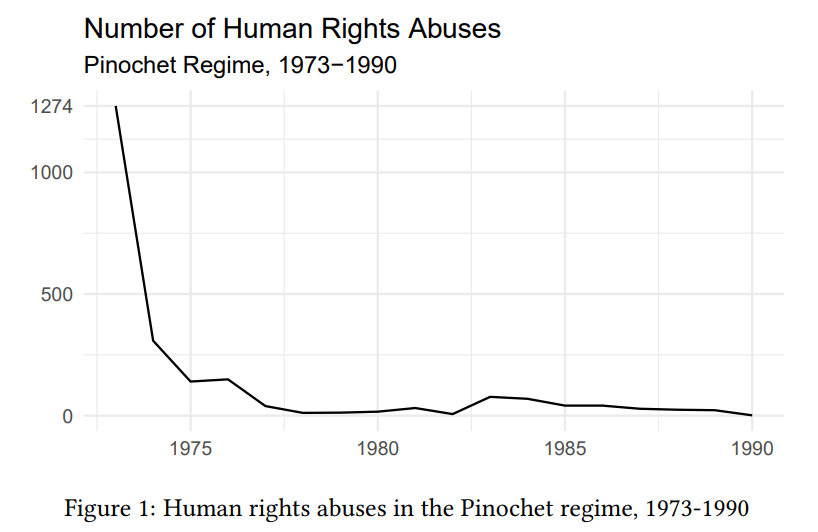

Manuel Contreras, the director of national intelligence and architect behind assassinations abroad, domestic kidnappings, and frequent tortures at home, believed the Chicago boys were intellectual traitors to Chile. The true goal of these upstarts who studied abroad was to deliver Chilean industries into the hands of international actors in order to line their own pockets. By 1975 he had collected “thick files on the personal activities of each of them.”

The American ambassador in an internal memo noted that the main opposition to personal rights and just criminal proceedings in Chile was Contreras. Contreras’ own story of power ended in 1977 when Pinochet dismissed him for pulling too hard on the leash. The standard theory is that Contreras brought too many diplomatic headaches with his human rights abuses and permissionless assassination of Chileans abroad. Political oppression should be subtler.

After Friedman’s visit, military statists started to lose ground and the Chicago educated economists gained ground. Pinochet starting appointing private citizens to high cabinet posts, not merely to advisory ones.

Consider the following dates of Chicago Boys assuming senior roles in government. This first round of major hires and promotions were all after Milton’s 1975 visit. I take this as evidence of a “Milton effect.”

Sergio De Castro: Minister of Economy 1975-76, Minister of Finance 1976-82.

Pablo Baraona: President Banco de Chile 1975-76, Minister of Economy 1976-78

Sergio De la Cuadra: VP Banco De Chile 1977-81

Alvaro Bardon: President Banco de Chile 1977-81

Miguel Kast: Director of Planning 1978-81

When I look at this data my initial thought is to conceive Friedman as a kind of voice of reason for the military government. Like a CEO who wants to change the org chart and operational structure but first wants someone from McKinsey to tell him to do it, Pinochet and his military apparatus needed the little push from this famous outsider to hand over the keys to economic reform to Sergio de Castro and his American educated colleagues. An outside voice can create permission and coordination within any regime.

It is not that Friedman and the Chicago boys coordinated their actions, rather, they both pushed in the same direction. Nor was Friedman the godfather of the reforms or the secret counselor to the Chicago boys. His influence is the more diffuse – like that of a major brick layer in the grand edifice, the edifice of monetarist economics and promotion of the price system view of the world. Milton was an architect of an edifice which the Católica academic economists also worked on and eventually put into practice.

Friedman’s Reward

Friedman’s reward for his candid advice to the Chilean people was protests at all his public appearances, an interruption at the Nobel Prize ceremony, and a general vitriol that he would visit this particular dictator.

At the Nobel Prize ceremony a young activist was able to use his father’s ticket to con a seat. Then he waited for a dramatic moment of silence after the introduction of Milton Friedman to King of Sweden. He stood up with great gesticulation and shouted, “Down with Capitalism.”

Friedman reflected on those events 25 years later for a PBS interview in 2000 and had this to say:

The Communists were determined to overthrow Pinochet. It was very important to them, because Allende’s regime, they thought, was going to bring a communist state in through regular political channels, not by revolution. And here, Pinochet overthrew that. They were determined to discredit Pinochet. As a result, they were going to discredit anybody who had anything to do with him. And in that connection, I was subject to abuse in the sense that there were large demonstrations against me at the Nobel ceremonies in Stockholm. I remember seeing the same faces in the crowd in a talk in Chicago and a talk in Santiago. And there was no doubt that there was a concerted effort to tar and feather me.

We know also that Friedman’s dealing with Chile were beneficent and nonpartisan. He refused honorary degrees from government run Chilean universities, stating that state involvement as his reason. Al Harberger vouches that Friedman stated over and over again his belief that decentralization of markets would undermine centralization in politics, including in his university speech “The Fragility of Freedom.” But there is some tension in this with what he said in Capitalism and Freedom. Autocrats may coexist with free markets for a time.

Furthermore he was directly helpful to one non-Chicago educated Chilean. Our cybernetics friend Fernando Flores, the Minister of Economics from the Allende government, had been in prison for three years and not allowed to leave the country. Friedman, never having met him, intervened on behalf of his freedom.

“Like many another friend of Chile, who is also a believer in human freedom and liberty, I have been greatly distressed by the restrictions on personal and human freedom in Chile that have been widely circulated in the West. . . . The immediate occasion for this letter is the case of a former Allende cabinet minister under detention in Chile, Fernando Flores Labra. . . . I have never met Mr. Flores personally and have had no direct contact with him. However, I have been led to inform myself about him. As I understand it, Fernando Flores is legally eligible for a US visa under US immigration laws, Stanford University has offered him a position in its Computer Science Department, and Chile has not granted him permission to leave the country.

“Freedom is indivisible. Greater economic freedom promotes and facilitates greater political freedom. But equally, greater political freedom promotes economic freedom and it contributes to economic progress and development.”

After Milton’s letter, Flores was released from prison and made his home at UC Santa Barbara. The Spanish language Wikipedia page credits Amnesty International and makes no reference to Friedman’s intervention.

1982 Financial Crisis

In 1982 the Latin American Debt crisis shook Central and South America. Chile was no different. What made the crisis especially bad for Chile was that they neither abolished the central bank and dollarized, nor maintained a floating rate. They pegged, and kept the same peg for two and half years. Why Sergio did this, I don’t know.

In the 60s he had written argumentative papers and engaged in great fracas in favor of a free floating rate. But now the currency is pegged and pinned and wriggling on the wall.

The banks borrowed dollars. They lent in pesos. The investments inflows decreased when oil dropped and copper dropped, so they borrowed more dollars as a bridge loan, until as commodity prices sunk the Andean skis went flying out from under them in an avalanche of bankruptcy, state bailouts, and unemployment.

Friedman had always been against a hard peg. And when the hard peg broke down it was not surprising to Milton that Chile was one of the countries greatly wounded by the crisis. Thus it was not Chicago school orthodoxy that made the 1982 crisis especially bad.

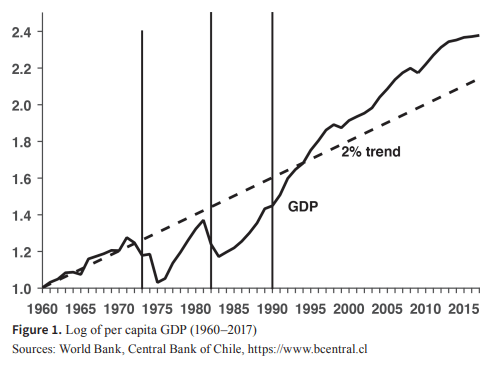

Al Harberger points out that although the Chilean decline was greater than the others, it’s rebound was also stronger.

The Chilean [crisis] was maybe deeper than the others for reasons of it having a large amount of debt to begin with and of this problem coinciding with a copper bust, but anyway, Chile led the continent in climbing out of this recession. It was the only debt-crisis country that got back to the pre-crisis levels of GDP before the end of the decade of the ’80s, so for most of the countries, it was the full decade that they called the “lost decade.” In Chile, it was the better part of it that was lost. But Chile was the first to come out. Chile came out growing at 5, 6 percent per year — and long after. You see, you can say that when you’re in a recovery period, you’re recovering lost ground, [and] it’s reasonable to think you’ll do that fast, but after you’ve recovered the lost ground and you’re going on, if you continue on the same or even increasing trajectory, that’s even more of a miracle. And that is all part of the Chilean picture.

GDP Growth

A Long-Expected Political Transition

In 1980 Pinochet’s government installed a new Constitution. But they held on firmly to the reins of power. Civil authority and citizen freedoms were weak at best.

Even in 1986 the Universities’ top level presidents and administrators were all military officers. Friedman wrote in protest to rector of the University of Chile, General Roberto Soto MacKenney.

“Friedman noted that he had received information that ‘suggests that the universities in Chile in serious danger of having their academic integrity and performance destroyed by the application of arbitrary and irresponsible force [by the military authorities],'” pg. 153.

The Pinochet regime imposed unfreedom.

After the 1982 crisis, Pinochet fired a bunch of people in economic management. He put in more old guard traditional import substitution economists. But when their policies failed to deliver a reduction to inflation and a return to employment, he went back to Católica and found the young guard of Chicago educated economists and put them in.

(I wonder about the internal process here.)

A second round of reforms followed: an independent central bank, privatization of the remaining government owned firms, and a slower paced reopening of the economy than the shock treatment of 1975. The political economy may have worked better because when Pinochet let go the direct reins of power through the referendum of 1988 the Christian Democratic party maintained and continued the basic reform program in 1990.

Pinochet left the presidency, but not power. He retained the position of commander-in-chief of army until 1998. When he went for back surgery in a London clinic in 1998 he was arrested while bedridden with extradition orders to go to Spain, creating an international incident, which is beyond the scope of my research. That satyr play will have to wait.

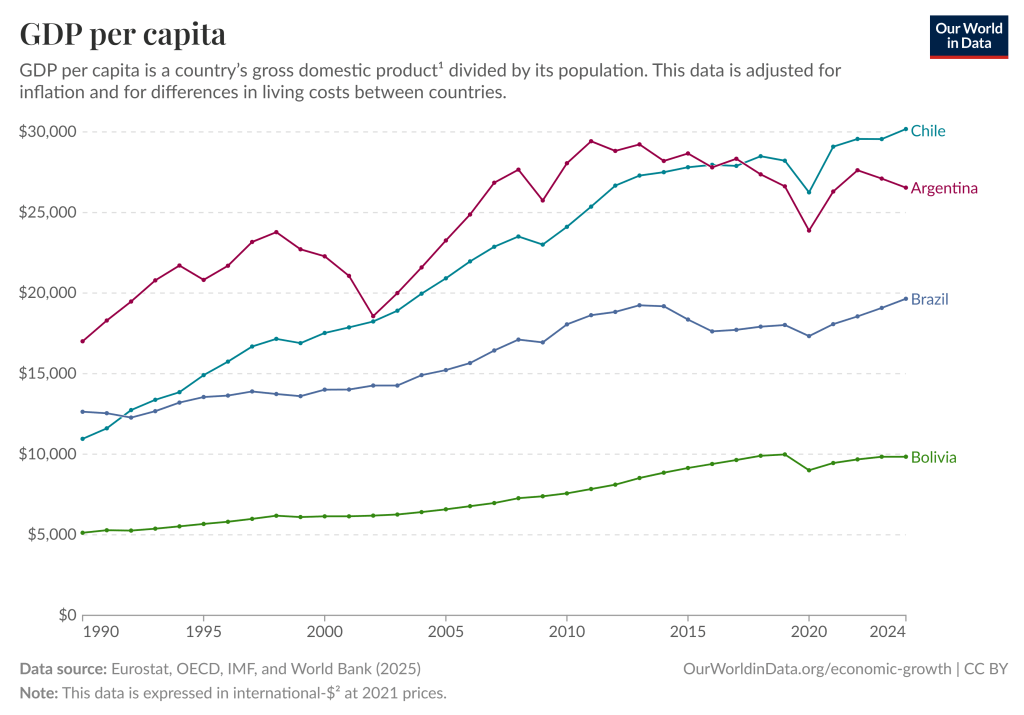

In 2002 Chile equaled Argentina in GDP per capita, and surpassed them clearly by 2018.

Lingering Questions

Remaining Questions I have are in buckets.

Technical questions:

- How big a problem was the peg during the Latin American debt crisis. Panama, which doesn’t have a central bank, was punished severely anyway. The other Latin American countries with crawling pegs were trounced. The U.S. sported -1.8% GDP growth! So is there really anything Chile could have done?

- In the 90s Chile put in place import holding rules on capital flows to make them park in the Central bank for a year. Is that a helpful move for preventing a repeat of 1982? Just because Stiglitz thinks so, doesn’t make him wrong.

- When reading the history of Japanese Finance Minister Matsukata Masayoshi, I was struck by how he altered the tax collection system regime to benefit the fiscal situation, namely by cutting back delays and increasing enforcement. He was still able in effect to decrease the debt issuance of silver-backed debt from a government that didn’t want to cut military spending. What was tax collection and the fiscal history of the dictatorship?

- Did Milton Friedman really sway the government officials or am I missing details about the regime which made the eventual promotion of civilians into ministries inevitable?

- Were there Mistakes in the speed and sequencing of the policy changes?

- There are constant arguments about the pension reforms in Chile. I’d like to know more about these (and other aspects of pension policy theory). The actuarial part of me is excited about this potentiality.

- Were there meaningful differences between the Bolivian fight against hyperinflation and Chile’s policies?

Dictator Club Questions:

- Did Spain’s slow liberalization make the politics of Chilean fast liberalization easier?

- What did Pinochet think of all this economics stuff? I have read once that a Spanish finance minister kept wanting to ask Franco permission to change some large policy. And Franco just waved his hand and said something to effect of “just don’t get me involved.”

- What did Pinochet do with his time?

- Did Peronism affect Chile?

- Did the Brazilian dictatorship affect Chile domestic strategy?

- How did Allende’s government exercise power?

- How much were Unidad Popular funded by outside sources?

- How did Pinochet think? Is it a miracle that a military government allowed these reforms?

- What percentage of time does inflation over 300% result in a coup?

Annotated Bibliography

Edwards, Sebastián. The Chile Project: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of Neoliberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023.

The lion’s share of my information came from this volume. The bibliography and endnotes were particularly instructive. Clearly the best book on the subject, especially for a serious general audience.

As part of my intellectual hygiene habits to avoid words that end in “-ISM” I’ve tried to be quite sparing in this article, Nonetheless “socialism” and “capitalism” rear their ugly heads. Similarly there’s no discussion of “neoliberalism” here, although Edwards’ book does an extended treatment of the topic.

Meiselas, Susan, ed. Chile from Within. Photographs by Chilean photographers, texts by Marco de la Parea and Ariel Dorfman. New York: Pantheon Books, 1991.

The photos from the military regime were powerful for evoking a sense of political oppression and the people who resisted it. But the book also talks about the abuelitas who resisted Allende and the abuelitas who resisted Pinochet (often the same!).

Piñera, José. “Salvador Allende’s Chile in Eleven Truths.” Archived at the Internet Archive. Accessed February 7, 2017.

.

God bless archive.org which preserves this excellent website by one of the honorary Chicago Boys. Through José’s website I was able to find the National Assembly’s condemnation of Allende.

De Castro, Sergio. El Ladrillo. Santiago: Centro de Estudios Públicos, 1992.

The original text of El Ladrillo. I haven’t read all of it yet due to my still plodding Spanish. But it is a tremendous framework document. Not nearly as economically technical as I expected. It’s more of a roadmap than a series of prewritten directives for different departments of the economy.

Silva, Carola Fuentes, dir. Chicago Boys. Documentary film. Chile, 2015.

Some good interview snippets, but I wish there was a lot more. It got me thinking about the political pressures and costs of working for military dictatorship and the long-term difficulty of maintaining a positive legacy. Sergio de Castro has had to “ignorance-wash” himself beyond credulity. But to do otherwise is suicidal not only to his reputation but also treasonous to his life’s work to provide good economic policy for Chile. I especially appreciated Ernesto Fontaine’s body language. His candor and “dgaf-iness” I found endearing.

Friedman, Milton, and Rose Friedman. Free to Choose. PBS documentary series. Episode 5, 1980.

This episode had a segment on Chile and included the protests against Friedman at the Nobel Prize ceremony. It was incredibly uncomfortable waiting for the young black-tie protestor to be escorted out.

Morozov, Evgeny. The Santiago Boys. Audio series, 2022.

This series tells the story of Allende’s economic attempt to make a new world free from capitalism. I found it full of good interview snippets, excellent production value, and masterful editorializing. Yet sometimes it was also one of the worst offenders under the banner of “things meant to make the reader think they know something when in fact they know little.” Nonetheless, it was a fun romp.

Whelan, James. Allende: Death of a Marxist Dream. Washington, DC: Regnery Gateway, 1981.

Features lots of interviews with military personnel and others from the coup days. I have barely dipped into it, but it seems to be a very valuable book. I got a much better sense of the scale of the near total public rejection of Allende’s government. And honestly it is just beautiful and excellent journalism.

Larroulet, Cristián, and Fernando Soto-Aguilar. Chile: Economic Freedom 1860–2007. Serie Informe Económico No. 197. Santiago: Libertad y Desarrollo, March 2009.

Caputo, Rodrigo, and Diego Saravia. “The History of Chile.” Working paper. Centre for Experimental Social Sciences, University of Oxford; Universidad de Santiago; Central Bank of Chile, 2021.

Freire, Danilo, John Meadowcroft, David Skarbek, and Eugenia Guerrero. Deaths and Disappearances in the Pinochet Regime: A New Dataset. Working paper, May 30, 2019.

Spanish language Wikipedia was also helpful for things it said and the things it did not say.

Thank you to Sam Enright and the Fitzwilliam for setting me on this quest. I believe this essay will prove one of most definitive outlines on these matters for the general reader — in spite my tone and tense switching and undoubtedly some errors I have made.